Miami vise

The managers of the Miami Herald acted harshly, rashly and timidly when they decided to fire columnist Jim DeFede in the emotional aftermath of a shocking suicide in the newspaper’s lobby.

There was enough tragedy for one day when Arthur E. Teele Jr., who was described by the Washington Post as “a spectacularly skilled and spectacularly flawed Florida political legend,” shot himself to death Wednesday in front of a potted palm the Herald’s marble lobby on Biscayne Bay. An explicit, four-column photo of scene was (appropriately) the centerpiece of the newspaper’s front page the next morning.

Five hours after the mortally wounded politician was rushed to the hospital, Mr. DeFede, a long-vigorous voice at the Herald, was fired at about 11 p.m. for admitting he had taped without consent one of two desperate final telephone conversations he had with Mr. Teele. It is illegal in most cases in Florida to tape a call without the permission of the other party.

In a television interview after his dismissal, Mr. DeFede said he knew it was illegal to tape the call but that he acted instinctively when he realized Mr. Teele was possibly suicidal. “The only reason the Herald knew about the tape was I came forward and told them,” Mr. DeFede told CBS4 News in Miami. “I realized I made a mistake and it was not something I should hide. I went to my bosses and said, ‘This is what happened. Where should we go from here?’”

According to an interview with Mr. DeFede reported by the Washington Post, the journalist says he discussed the incident with management after “being assured by one of the paper's lawyers, Robert Beatty, and by publisher Jesus Diaz that he had attorney-client privilege.” The Post quoted Mr. DeFede as saying the attorney promised, "The Herald will support you."

Later that night, Mr. DeFede was on the street.

The abrupt cashiering of the columnist has sparked a firestorm of protest and second-guessing, including an instantly posted blog where hundreds of journalists have added their names to a petition urging the Herald to reinstate Mr. DeFede.

I am adding my name to the list, because, first and foremost, there is reasonable doubt about whether Mr. DeFede actually broke the law. I also think the punishment didn’t fit the crime, if indeed there was one.

In its state-by-state guide to the laws affecting the activities of reporters, the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press says at least one appellate ruling in Florida found “business telephones are not the type of devices addressed” in the law that prohibits unauthorized taping. Further, RCFP reports that the law does not necessarily require the consent of a person “who does not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in that communication.”

When a sophisticated public figure telephones a high-profile columnist of the biggest newspaper in town before committing suicide in the lobby of the newspaper, the caller could not have had a “reasonable expectation of privacy in that communication.” In fact, Mr. Teele’s actions suggest he very much wanted to make a dramatic public statement.

Notwithstanding Mr. DeFede’s professional role and legal obligations, he reacted the way one human being might respond to another in a moment of crisis. Though his judgment may have been flawed, his intentions were pure when he made the snap decision, in an emotional and terrifying instant, to record a call from a distraught man he says he regarded as personal friend.

Mr. DeFede deserved to be cut some slack.

Instead, he was hastily tried, convicted and executed by mangers who themselves were understandably unhinged by the horrifying event that had unfolded, literally, at their front door only hours earlier.

If this was a single, aberrant incident, then the Herald’s managers owed it to Jim DeFede, and themselves, to consider a less drastic alternative than the corporate equivalent of capital punishment. There were many ways for Mr. DeFede to admit his error, accept his punishment and move on, leaving him to shoulder any personal legal consequences.

The paper could have denounced his act, punished him with a suspension and put him on final warning not to do it again. This would have left the Herald reasonably in the clear from a legal point of view, while upholding its reputation as a law-abiding, fair minded and compassionate institution.

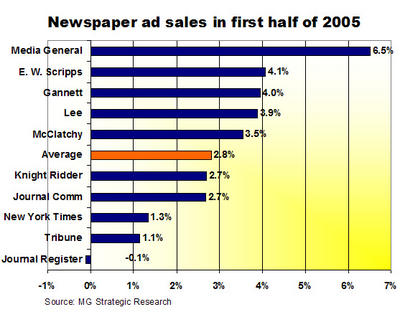

So, what was behind the rush to summary judgment? Some say it was Mr. DeFede’s criticism of the management of the newspaper and its owner, Knight Ridder. “From inside the newspaper, Mr. DeFede became one of its most stinging critics,” reported the Washington Post. The conspiracy theory is too facile.

Another possibility is that there is more to the story than meets the eye. Could Mr. DeFede have been warned in the past about improperly recording calls? We have no way of knowing and, to be absolutely clear, I am not suggesting this is the case. If those were the circumstances, however, then management would have had no choice but the one it took.

If this was an isolated case of poor judgment by Mr. DeFede, then the simplest interpretation of events is that management acted impetuously, impaired in the heat of the moment by fear and misplaced, displaced anger.

Was management worried about legal liability? As discussed above, the legal risk is arguable.

Was management fearful of economic consequences in the form of criminal penalties or a civil damage suit and the legal costs associated with them? If I understand the statute correctly, the victim of an illegally recorded call can be awarded no more than $1,000 in compensation. Given that the victim is dead and that he and his estate suffered no evident damage as a result of the taping incident, the risk of a viable lawsuit seems limited. An amount equal or greater to the legal fees saved by rapidly firing Mr. DeFede probably will be expended to defend the Herald against any wrongful-termination lawsuit the columnist might be motivated to file.

Was management worried about bad publicity? What could be worse than this?

In its haste to jettison Mr. DeFede, the Herald has eroded significantly the bond of trust and loyalty with its employees that makes any business effective, be it a major metropolitan newspaper or a hamburger stand.

Loss of confidence in the employer is particularly corrosive in the newsroom, where a cautious and cowed staff is antithetical to the conditions required to put out a compelling product that serves its community and remains economically vibrant.

The management of the Herald didn’t do itself much good in dispatching Mr. DeFede with such dispatch. And it didn’t do right by him, either.