Struggling industry throttles newspaper metrics

Unable to arrest years of declining ad sales and sliding print circulation, two key trade groups representing the newspaper industry have done the next best thing:

They effectively have stopped reporting on the metrics that make it possible to measure – and, therefore, understand and manage – the industry’s ongoing challenges.

Earlier this year, the Newspaper Association of America, an industry-supported trade organization, decided to stop producing the quarterly revenue reports that have charted the advertising slump that has carved aggregate industry revenues from a record $49.4 billion to $22.3 billion in 2012.

As reported here, my analysis shows that ad sales slipped about 5.5% in the first six months of the year. Assuming the industry does no better or worse in the last half of the year, it is on track to deliver approximately $21 billion in ad sales for all of 2013.

The NAA, which publishes sales records dating to 1950 here, promises to release a once-a-year revenue report scheduled to debut in March, 2014.

While the revenue picture may come into greater focus next spring, a series of changes in the way newspapers report readership has made it impossible to authoritatively compare ongoing changes in circulation.

As has been customary for years, the Alliance for Audited Media, which formerly was known as the Audit Bureau of Circulation, today announced the publication of the second of its semi-annual circulation reports. But this time, unlike all the others, the organization gave no clue as to whether circulation had gone up, down or sideways in the six-month reporting period.

Because publishers no longer are “required to report the same information, it is not possible to come up with a macro [circulation] number,” said Neal Lulofs, the executive vice president of AAM in a telephone interview.

Owing to a series of changes adopted by the industry-funded organization over the years, publishers no longer have to provide a five-day average of daily circulation. They also have the liberty of counting a woman who reads the paper in print, on her office computer, on her personal laptop, on her tablet and on her smartphone as five separate subscribers.

Some newspapers take advantage of these options and others do not, eliminating seemingly forever the possibility of comparing apples-to-apples data across the industry – or even from year to year for the same publication, if it changes its reporting standards over time.

Notwithstanding the limitations imposed by the inconsistent data, a few hardy analysts have been trying to gauge the public appetite for print newspapers as it has declined over the years.

One of them, Ken Goldstein of Communications Strategies in Canada, pegs weekday print circulation in the United States at about 38 million copies, as compared with the 43.4 million subscribers reported in the Editor & Publisher Yearbook for 2012.

The E&P number, which closely matches the last-available AAM data published this spring, appears to include both print and digital editions. Thus, the E&P data are not precisely comparable to Goldstein’s estimate.

Setting aside the discrepancies in the admittedly imperfect data, one thing is clear: Newspaper circulation today is at, or below, its lowest level in modern history.

The oldest available records from E&P show that weekday newspaper circulation averaged 41.4 million papers per day in 1940, as compared with 38 million to 43 million today. Daily circulation, btw, peaked at 63.3 million in 1984.

But there is a big difference between 1940 and now: The population is a lot larger.

Back in 1940, newspaper penetration actually surpassed 100% of households, because some families took more than one paper per day. Today, with the number of households three times greater than in 1940, there’s a paper in only one out of three homes.

Omidyar’s big, bold bet on next-gen news

First, came Warren Buffett. Then, Jeff Bezos. Now, Pierre Omidyar has become the third prominent billionaire to try his hand at finding a popular and profitable business model for funding quality journalism in the digital era.

Apart from the common bond they share with a collective net worth approaching $100 billion, each of the business superstars is pursuing a distinctly different path in the quest for the elusive next-gen news model, as discussed more fully in a moment. Given their divergent strategies, could they all be right? Only time will tell.

But there’s no doubt that their energy, creativity and considerable wealth are welcome at a time that the digital revolution has driven the traditional purveyors of the news from distress to distraction to dysfunction to divestiture.

With unquestionable entrepreneurial chops and demonstrated investment acumen, the three billionaires are bringing far more than bulging checkbooks to the challenge of how journalism will be funded and practiced in an age when ever-changing technologies are unhinging the ways that consumers get and, increasingly, give the news.

The techno-tsunami has cut newspaper revenues by more than half, has all but killed Newsweek and continues to dangerously fragment commercial broadcast audiences. As the media behemoths tumble, the investments they historically made in funding journalism have crumbled (details here and here).

Now, Buffett, Bezos and Omidyar (plus a few others), are stepping up to try to figure out how to pay for real journalism, as opposed to jiggly GIFs, for the generations to come.

Each of the trio is taking a markedly different approach. Buffett, who has assembled a portfolio of more than five-dozen newspapers in two years, is aiming to refine and preserve the legacy publishing business. We’ll call him The Protector. Bezos almost certainly will try to move his newly acquired Washington Post away from its heavy reliance on print advertising and circulation to a state-of-the art digital business model. We’ll call him The Pivoter. Taking a third path, Omidyar announced last week that he intends to launch a bottoms-up digital model to create and distribute the news. We’ll call him The Pioneer.

Omidyar’s nascent, and evidently still evolving, effort looks to be the boldest, and riskiest, yet. To understand the challenges and opportunities he faces, it helps to see where the others are placing their bets. So, let's start at the beginning:

The Protector. Buffett, whose fortune is estimated at $58.5 billion by Forbes, was the first of the Big Three to plunge into the publishing business, buying the Omaha World Herald, his hometown paper, in 2011 with $200 million of the more than $35 billion in the coffers of Berkshire Hathaway, his legendary investment company. Within a year, Buffett’s newly formed BH Media spent a couple of hundred million more dollars to scoop up dozens of small and medium newspapers in relatively isolated and defensible markets. Eschewing metros like the Washington Post (where he has been a long-time stockholder and board member), Buffett professes to be so fond of newspapers that he will buy them even when their “economics” fall “far short of the size threshold we would require for the purchase of, say, a widget company.” As a fiduciary responsible to his shareholders, he is bound to protect the profitability of his assets to preserve, if not enhance, their value. This puts him in the position of being a Protector of the traditional, 20th Century publishing model, not an innovator who is likely to blow it up.

The Pivoter. Amazon-founder Jeff Bezos jolted but largely delighted the journalism community when he purchased the Washington Post with $250 million of his own money in a deal that closed earlier this month. After getting over the shock of learning that they would be deprived of the long-running patronage of the Graham family, staffers of the iconic newspaper viewed the acquisition as a vote of confidence in the medium, if not themselves. But Bezos, who is the first digital native to buy a newspaper, didn’t build a $27.2 billion personal fortune by sticking to the conventional rules of book selling, retailing, web hosting, media delivery or any of the other industries he has disrupted. He undoubtedly plans to use the D.C. presence, journalistic resources and prestige of the Post to find new ways to build and monetize audiences in more high-tech ways than putting ink to paper. Though he has to tread carefully as he repositions the business on the fly (as discussed here), Bezos is pursuing the path of a Pivoter as he endeavors to migrate from a print-based past to a profitably-pixelated future.

The Pioneer. The least affluent of the billionaires with only $8.7 billion in personal assets, Omidyar last week declared that he would put at least $250 million into building a global network of journalists to deliver news on a platform optimized for the digital age. He said he chose the sum of his investment because it was what he would have paid, if he, instead of Bezos, had chosen to buy the Washington Post. Based on his thoughts here and excellent reporting from Jay Rosen here, Omidyar appears to be trying to find a way to capitalize on the two major forces reshaping the journalistic landscape and the appetite for news: (1) Anyone, anywhere can publish anything at anytime and (2) users can control the content they consume at the time, place and platform of their choosing. The trick, as the eBay founder well knows from starting a for-profit Honolulu news site called Civil Beat, is to find an efficient, popular, scalable and eventually profitable model to that both captures the public’s fancy and serves the public interest with bold and consequential reporting. To kick things off in a big way, Omidyar is hiring Glenn Greenwald and the other journalists who broke the NSA data-scraping story. Because he is starting an entirely new kind of business with little more than a blank white board, Omidyar, who promises to be personally active in building the still-unnamed venture, clearly can be characterized as a Pioneer.

The saying here in Silicon Valley is that you can spot a pioneer because she’s the one with arrows in her back. But some pioneers are better at dodging arrows than others. Fortunately for those who care about journalism, Jeff Bezos and Pierre Omidyar are two of the best of them.

Newspaper sales dive enters 8th straight year

As digital advertising sales soared 18% to a record high in the first six months of this year, the revenues of the publicly traded newspaper companies slipped an average of 5.5% to enter an eighth year of unabated decline.

Paced by a 145% increase in mobile ad sales, digital volume hit a half-year high of $20.1 billion, according to the Interactive Advertising Bureau, a trade organization. The sum is nearly equal to the $22.3 billion in sales collectively produced by the nation’s 1,382 dailies for all of 2012.

Assuming digital and newspaper sales pursue the same trajectory for the balance of the year, then digital revenues for the full 12 months will be more than twice the revenues produced by newspapers, whose aggregate sales hit a record $49.4 billion as recently as 2005. In a measure of the dizzying pace at which the marketplace is shifting, interactive revenues were $12.5 billion in 2005.

As illustrated in the chart below, the growth in digital advertising is taking oxygen from the other legacy media, too.

While broadcast television sales grew by 6.4% in the first half of the year, magazine sales gained 0.4% and radio sales were flat. The data were provided by their respective industry associations, the Television Bureau of Advertising, the Association of Magazine Media and the Radio Advertising Bureau.

In the absence of information formerly reported by the trade association representing the newspaper industry, the 5.5% decline in publishing revenues is based on an analysis of the financial statements of the 10 publicly traded companies that own domestic newspapers.

The revenues of the group, which includes A.H. Belo, Gannett, GateHouse Media, Journal Communications, Lee Enterprises, McClatchy Co., New York Times Co., Scripps, Tribune Co. and the Washington Post Co., represent about a third of the nation’s newspapers. Because their holdings collectively include everything from tiny weeklies to some of the largest metros, the performance of the group probably is a fair indicator of where ad sales are going.

But it will take until next spring before we know for sure, because the Newspaper Association of America has stopped producing the quarterly revenue reports that had been chronicling the stubborn revenue decline that has been under way since April, 2006.

Although the association’s online archives contain sales data dating back to 1950, the quarterly revenue reports produced by the NAA since 1971 are not going to be updated any more, according to Brooke Brennan, a spokeswoman for the association.

“The NAA recently switched to a robust reporting that looks holistically at all of the member papers,” said Brennan in an email. “Due to the fact that the reporting is much more involved, it was determined that it would be best to focus the effort around a yearly report.”

Until more holistic information is available, here is what we know:

7 tumultuous years for Tribune newspapers

A directive to cut up to $100 million in spending at the Tribune Co. newspapers is but the latest challenge to a group of iconic titles that have been twisting in the wind for seven of the most tumultuous years ever experienced by the publishing industry.

The budget cuts in store for the Chicago Tribune, the Los Angeles Times and six other dailies published by the company add to the uncertainty, anxiety and indecision that have distracted staffers at the publications since a series of convulsive – and inconclusive – changes in ownership and management commenced way back in 2006. Sadly, as discussed in a moment, there is still no end in sight.

The timing of the ongoing cluster-kerfuffle could not be worse, because the managers and employees of the newspapers ought to be spending their days developing new products, acquiring new audiences and building new revenue streams to meet the abundant challenges of the digital era.

Instead, they are wondering who will own the company, who will be in charge, what they will be asked to do and what might happen next. Not the least of their concerns is whether they will have jobs in the next week, next month or next year. More on this in a moment. First, the background:

The seven-year ordeal for the Tribune newspapers began in September, 2006, when the publicly held company kicked off the process of putting itself up for sale as shareholders feuded over its ebbing stock price.

The yearlong hunt for a buyer ended when real estate mogul Sam Zell acquired the company in December, 2007, with $13 billion in debt and only $315 million of his own $4 billion fortune. Zell promptly put the company into a novel, privately held employee stock ownership plan that eventually resulted in a $32 million payout to employees whose retirement funds had been caught up in the scheme. Along the way, he memorably scolded the journalists at the Washington bureau of the Los Angeles Times for not producing any revenue.

Zell, who was not beyond using salty language (NSFW video) from time to time, installed an “Animal House”-style management team headed by former radio executive Randy Michaels, whose antics prompted a front-page spanking in the New York Times that was titled: “At Flagging Tribune, Tales of Bankrupt Culture.” Michaels and his crew eventually were sent packing, including Chief Innovation Officer Lee Abrams, who was suspended after seeking to stimulate the creativity of his colleagues by sharing a raunchy Onion video involving “2,000 pounds of sluts.”

Zell’s effective control of Tribune lasted but 12 months, as the ill-conceived, over-leveraged and poorly executed acquisition drove the business into an epic, four-year bankruptcy. In addition to generating more than half a billion dollars in legal and other fees, the bankruptcy resulted in a never-ending series of expense cuts and layoffs.

As soon as the company exited bankruptcy at the start of this year, its new chief executive, broadcaster Peter Liguori, immediately put the newspaper division up for sale. When the hunt for a buyer failed, Liguori decided in July to sever the struggling publishing assets from the more lucrative television businesses operated by the Chicago-based company (as explored further here and here).

In the latest twist, Liguori last month ordered a fresh round of spending cuts to bolster the profits of the newspapers for a spinoff that remains an untold number of months in the future. Chicago media expert Robert Feder reported that Liguori wants $100 million in annual savings from the newspapers to commence by Dec. 1. Following Feder’s scoop, the Chicago Tribune said the target is $75 million to $100 million.

The tribulations at the Tribune Co. in the last seven years could not have come at a worse time. The period happened to be the unkindest in history for American newspapers, with industry-wide advertising sales – the primary revenue stream – tumbling from a record $49.4 billion in 2005 to $22.3 billion in 2012.

Suffering to roughly the same extent as its peers, Tribune’s publishing revenues dived from $4.1 billion in 2006 to $2.0 billion in 2012, according to the company’s financial statements. In fairness, it must be noted that approximately $400 million of the revenue decline can be attributed to the sale of Newsday to Cablevision in mid-2008 in a complicated transaction that subsequently saddled Tribune Co. with tax issues that could cost it some $273 million in back levies and penalties.

In the second quarter of this year, Tribune’s publishing revenues fell 4% to $470 million from the level achieved in the same period in 2012. While Tribune has provided only fragmentary financial results for the newspaper division since its exit from bankruptcy, the company reported that the division in the second quarter of this year produced $75 million in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) vs. $45 million in the prior year.

Assuming the newspaper division replicated the second-quarter results for each quarter of this year, then it would deliver nearly $1.9 billion in revenues and $300 million in profits over the full 12 months. At that rate, its EBITDA of nearly 16% would surpass the 13% average produced by the other publicly held newspaper companies.

Even though Tribune Co. appears to be doing as well – if not somewhat better – than most other newspaper publishers, Liguori is calling for tens of millions of additional expense reductions to plump the bottom line. To put the full $100 million target in perspective, the sum is estimated by informed sources to be roughly equal to the combined newsroom budgets of the Chicago Tribune and Los Angeles Times.

Where will Tribune’s publishers find up to $100 million in additional savings?

In a staff meeting last week, Ligouri said $800 million in expenses already had been cut from the newspaper division in recent years, according to Feder. The Chicago newsman further reported that the chief executive wants to “drive forward toward the most functional group we can that creates the best papers on the planet.”

To shrink spending over the years, the Tribune Co., like most publishers, has cut page sizes, news hole, marketing and headcount. As but one benchmark, informed sources estimate that the news staff of the Los Angeles Times numbers about 570 (this is corrected from an earlier undercount) today vs. a peak of 1,300 in 2000.

Although payrolls already have been pared from historic levels, staffing is bound to come under further scrutiny, because so many other savings already have been implemented through outsourcing, production consolidation, administrative streamlining and similar one-time measures.

While the Tribune does not report the current number of employees in the newspaper division, it did tell shareholders in 2006 that it had a total of 21,000 employees across all units with 17,800 individuals in the publishing division. Today, the company has 11,500 employees across all divisions, according to its public declarations.

Assuming the staff cuts over the years were made proportionally by division, then the newspapers at this time collectively would employ approximately 9,500 individuals. This estimate probably is high, because it doesn't take into account the hundreds of employees who left the company when Newsday was sold. The Tribune spokesman did not respond to a request for the current news headcount.

With more cuts potentially in the offing, employees accustomed to years of anxiety are likely to face more sleepless nights.

Beyond the inestimable emotional, financial and sometimes physical strains imposed on employees by the long-running uncertainty at the company, you can’t help wondering how much the value of the publishing division itself has been weakened.

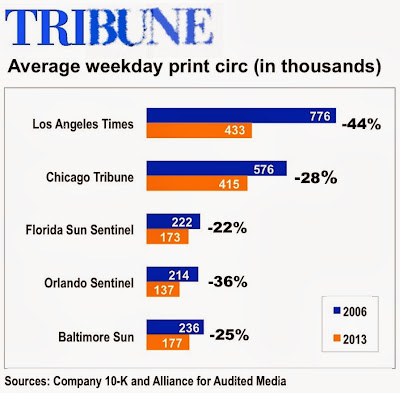

As illustrated in the table below, the average weekday print circulation of the five largest Tribune dailies has dropped by 34% since 2006. The Los Angeles Times, whose print readership has declined 44% since 2006, experienced the biggest drop of the group.

In fairness, it must be noted that the circulation slide mirrors an industry-wide trend. But the deep readership and revenue declines suffered by newspapers in the last few years underscore the need for publishers to focus on pivoting as fast as possible away from the waning print model.

By all outward appearances, the continuing corporate convulsions at Tribune have made the necessary focus impossible to achieve. Lacking day-to-day stability, clear-cut strategic goals, consistent management and steadfast ownership, some of the nation’s largest and most important newspapers have cycled fruitlessly, and sometimes aimlessly, as a host of digital competitors have sapped their audiences, their revenues and the power of their once-formidable brands.

This is a not only tragedy for the employees and the communities they serve. It’s likely to be a tragedy for Tribune’s investors, too.

Digital media get ready to get more personal

Say good-bye to one-size-fits-all content and advertising. The age of personalization is arriving in the digital media, and it will change everything about what we read, where we eat, what we buy and even how we get to work.

There is a race under way in Silicon Valley (and beyond) to do an ever-better job of tracking, archiving and analyzing consumer activity on desktops, laptops, tablets, smartphones, smart TVs and other interactive devices, so as to deliver increasingly customized user experiences.

From the tech giants to any number of start-ups, the stated goal of these activities is to improve consumer satisfaction. And that’s true, because user-specific content generates more frequent visits and longer dwell times than generic yadda-yadda.

But the real objective of the feverish development is to do a better job of targeting advertising to consumers based on who they are, where they are, what they say they like and – significantly – the additional actionable information that can be inferred from the digital breadcrumbs they leave behind.

The personalized delivery of content and advertising, of course, is the polar opposite of the monolithic digital products produced at most newspapers. To date, the industry has lacked the imagination, technical skill and capital to move toward the sophisticated, data-driven publishing models being developed by the digital powerhouses.

But there’s fresh hope that publishers can catch up, thanks to the acquisition of the Washington Post by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. More on that in a moment. First, the background:

The personalization process starts with the granular tracking of everyone’s movements as they ply the web. How granular? Here’s a taste of what Google knows about my activity in the last four years:

At 10:11 a.m. on June 19, 2010, I shopped at Walmart.Com for a Garmin navigation unit. I can’t recall if I bought it. At 11:52 a.m. on March 21, 2011, I searched for news about Justin Bieber, for reasons I am at a loss to explain. At 2:20 p.m. on Dec. 8, 2012, I watched a video of Mark Bittman preparing potato pancakes. The latkes were terrific. At 2:02 p.m. on Aug. 21, 2013, I grabbed a prized exit-row seat for an upcoming flight on United Airlines.

I am not sure what Google can make of these and the thousands of other searches that it meticulously recorded over the years. At this writing, Google might not, either. But you can rest assured that some of the brightest minds in the world are building complex algorithms to match my activities with other Garmin-Bieber-Bittman-United aficionados to see what I might do next. And, of course, what I might buy.

Search activity is only one of the dimensions being mined for marketing insights. Leveraging the largest compendium of self-published personal data in history, Facebook is monitoring, mapping and matching everything it knows about you with everything it knows about your friends, relatives, business associates and other acquaintances in your social network.

And the reason, as forthrightly – but ungrammatically – explained at the Facebook website, is this: “Everyone wants to know what their [sic] friends like. That’s why we pair ads and friends – an easy way to find products and services you’re interested in, based on what your friends share and like.”

The third, and perhaps most revolutionary, dimension in personalization is your precise location. Whether you are looking for a burger, a bicycle or a barber, a search on a desktop browser or a smartphone map not only returns a list of nearby establishments but also includes user reviews, directions to the business and – no surprise – advertising.

State-of-the-art personalization systems on mobile devices don’t rely on you to report your whereabouts or your craving for a Frappuchino. By monitoring your calendar, the weather, your contact list, traffic, retail transactions and the other data persistently captured on your smartphone, tablet or (soon) Google Glass, these devices in the not-too-distant future will wake you early because it is raining, will recommend the fastest route around the wreck on the freeway and will have a prepaid Frap waiting at the nearest Starbuck’s.

As smart devices manage the logistics of your life, the information will be combined with your reading preferences, search patterns, social activity, shopping history and other data to feed you a steady stream of content and commercial information tuned to who you are, where you are and, increasingly, what you are likely to do next.

There’s no better example of the phenomenon than Amazon’s ability to recommend the right knives to go with a cookbook or the perfect accessories to outfit a new camera. With Jeff Bezos turning his attention – and a bit of his $25 billion fortune – to newspapering, he is bound to bring the power of personalization to the news biz.

If other publishers are nice to him, he might share what he knows.

But the real objective of the feverish development is to do a better job of targeting advertising to consumers based on who they are, where they are, what they say they like and – significantly – the additional actionable information that can be inferred from the digital breadcrumbs they leave behind.

The personalized delivery of content and advertising, of course, is the polar opposite of the monolithic digital products produced at most newspapers. To date, the industry has lacked the imagination, technical skill and capital to move toward the sophisticated, data-driven publishing models being developed by the digital powerhouses.

But there’s fresh hope that publishers can catch up, thanks to the acquisition of the Washington Post by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. More on that in a moment. First, the background:

The personalization process starts with the granular tracking of everyone’s movements as they ply the web. How granular? Here’s a taste of what Google knows about my activity in the last four years:

At 10:11 a.m. on June 19, 2010, I shopped at Walmart.Com for a Garmin navigation unit. I can’t recall if I bought it. At 11:52 a.m. on March 21, 2011, I searched for news about Justin Bieber, for reasons I am at a loss to explain. At 2:20 p.m. on Dec. 8, 2012, I watched a video of Mark Bittman preparing potato pancakes. The latkes were terrific. At 2:02 p.m. on Aug. 21, 2013, I grabbed a prized exit-row seat for an upcoming flight on United Airlines.

I am not sure what Google can make of these and the thousands of other searches that it meticulously recorded over the years. At this writing, Google might not, either. But you can rest assured that some of the brightest minds in the world are building complex algorithms to match my activities with other Garmin-Bieber-Bittman-United aficionados to see what I might do next. And, of course, what I might buy.

Search activity is only one of the dimensions being mined for marketing insights. Leveraging the largest compendium of self-published personal data in history, Facebook is monitoring, mapping and matching everything it knows about you with everything it knows about your friends, relatives, business associates and other acquaintances in your social network.

And the reason, as forthrightly – but ungrammatically – explained at the Facebook website, is this: “Everyone wants to know what their [sic] friends like. That’s why we pair ads and friends – an easy way to find products and services you’re interested in, based on what your friends share and like.”

The third, and perhaps most revolutionary, dimension in personalization is your precise location. Whether you are looking for a burger, a bicycle or a barber, a search on a desktop browser or a smartphone map not only returns a list of nearby establishments but also includes user reviews, directions to the business and – no surprise – advertising.

State-of-the-art personalization systems on mobile devices don’t rely on you to report your whereabouts or your craving for a Frappuchino. By monitoring your calendar, the weather, your contact list, traffic, retail transactions and the other data persistently captured on your smartphone, tablet or (soon) Google Glass, these devices in the not-too-distant future will wake you early because it is raining, will recommend the fastest route around the wreck on the freeway and will have a prepaid Frap waiting at the nearest Starbuck’s.

As smart devices manage the logistics of your life, the information will be combined with your reading preferences, search patterns, social activity, shopping history and other data to feed you a steady stream of content and commercial information tuned to who you are, where you are and, increasingly, what you are likely to do next.

There’s no better example of the phenomenon than Amazon’s ability to recommend the right knives to go with a cookbook or the perfect accessories to outfit a new camera. With Jeff Bezos turning his attention – and a bit of his $25 billion fortune – to newspapering, he is bound to bring the power of personalization to the news biz.

If other publishers are nice to him, he might share what he knows.

© Editor & Publisher