Job 1 for newspapers: Audience development

While strategic audience development ought to be the top priority at every newspaper, efforts toward fulfilling this vital mission are fitful and far between at many publications. This has got to change, if the industry intends to sustain its strength.

The bad news for newspapers, as discussed here, is that a significant majority of the adults in the typical community don’t subscribe to the paper in either its print or digital incarnations. But the flip side of this problem is that the abundant population of non-readers in every community represents a substantial base of potential consumers for the transformative and delightful new products that publishers could bring to market – if they put their minds to it.

For the avoidance of doubt, a static, iPad-friendly PDF of the day’s print edition does not, IMHO, qualify as a transformative and satisfying digital product.

It’s not that newspapers neglect audience building. They don’t. But their outreach is aimed almost exclusively at capturing the increasingly rare customer who reliably pays for print or digital access for months, if not years, on end. Those are great customers and any business would be glad to have them.

But the population of steadfast loyalists is dwindling, as modern consumers take advantage of the digital media to customize the news, entertainment and information they ingest. Given shifting consumer preferences, newspapers need to think differently, if not to say obsessively, about how to serve – and profit – from individuals who don’t look, think or behave like traditional subscribers. Unfortunately, most newspapers don’t.

Here’s why they should:

:: Falling readership. Since peaking at 63.3 million subscribers in 1994 (the year before the Internet entered the public consciousness), weekday newspaper circulation today is 38 million to 43 million, as detailed here. Back in 1994, 63.5% of American households subscribed to newspapers, according to an analysis of census data. Today, barely one in three homes take a newspaper.

∷ Rising competition. Modern consumers are hooked on the power conferred by the digital media to pick and choose what, where, when and how they get news and other information. The Pew Research Center last year found that two-thirds of Americans visited upwards of three or more outlets to keep up with current events. Twenty percent of urban dwellers accessed six or more news sources, while 11% of rural residents consulted half a dozen or more sources.

∷ Demographic drift. Most young consumers simply don’t dig newspapers, leaving publishers with ever-older audiences that eventually will age to extinction. The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University earlier this year reported that 55% of individuals under the age of 35 preferred the digital media as their primary news source, as compared with 5% in the same age category who preferred print.

Because there is no reason to believe these trends are likely to reverse, publishers hoping to sustain and reinvigorate their valuable franchises need to concentrate on finding new products and services to attract the readers they need – and the advertisers they want.

Newspapers can create transformative and delightful products across the growing range of digital platforms by leveraging their unmatched content-creation capabilities, vast archives, unrivaled local marketing power and the deep commercial relationships they possess in each of the communities they serve.

What audiences? What products? What platforms?

The answers to those vexing questions will be revealed only after publishers invest the time and money necessary to develop thoughtful strategic plans that take into account local market conditions, the competitive forces arrayed around them, and the unique strengths and weaknesses of their respective organizations. Equipped with well-wrought strategic plans, publishers can invest wisely and confidently in opportunities to attract new audiences and revenue streams.

As mission-critical as strategic planning and audience building ought to be, these missions fail to be accorded the priority they deserve at many newspapers. Some newspapers delegate “audience” to the editor, who somehow is supposed to fix things by intuitively producing the “right” sort of content. Some publishers assign audience development to the circulation manager, who somehow is supposed to boost subscriptions while curbing cancellations. Some papers allocate audience development to the marketing department, whose staffing, research and/or promotional budgets often are the first to be cut in moments of financial distress. At many newspapers, these missions aren’t even explicitly on the radar at all.

When the development of transformative and delightful products is left largely to chance, the outcome is unlikely to be auspicious, because successful innovations seldom emerge from seat-of-the pants hunches, scattered responsibilities and episodic tactical skirmishes.

Success requires a well-researched, well-conceived, well-articulated and well-communicated strategic plan that is the responsibility of everyone in the building. At most newspapers, this approach not only would be transformative but also would make life more delightful than it has been in years.

© 2013 Editor & Publisher

But the population of steadfast loyalists is dwindling, as modern consumers take advantage of the digital media to customize the news, entertainment and information they ingest. Given shifting consumer preferences, newspapers need to think differently, if not to say obsessively, about how to serve – and profit – from individuals who don’t look, think or behave like traditional subscribers. Unfortunately, most newspapers don’t.

Here’s why they should:

:: Falling readership. Since peaking at 63.3 million subscribers in 1994 (the year before the Internet entered the public consciousness), weekday newspaper circulation today is 38 million to 43 million, as detailed here. Back in 1994, 63.5% of American households subscribed to newspapers, according to an analysis of census data. Today, barely one in three homes take a newspaper.

∷ Rising competition. Modern consumers are hooked on the power conferred by the digital media to pick and choose what, where, when and how they get news and other information. The Pew Research Center last year found that two-thirds of Americans visited upwards of three or more outlets to keep up with current events. Twenty percent of urban dwellers accessed six or more news sources, while 11% of rural residents consulted half a dozen or more sources.

∷ Demographic drift. Most young consumers simply don’t dig newspapers, leaving publishers with ever-older audiences that eventually will age to extinction. The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University earlier this year reported that 55% of individuals under the age of 35 preferred the digital media as their primary news source, as compared with 5% in the same age category who preferred print.

Because there is no reason to believe these trends are likely to reverse, publishers hoping to sustain and reinvigorate their valuable franchises need to concentrate on finding new products and services to attract the readers they need – and the advertisers they want.

Newspapers can create transformative and delightful products across the growing range of digital platforms by leveraging their unmatched content-creation capabilities, vast archives, unrivaled local marketing power and the deep commercial relationships they possess in each of the communities they serve.

What audiences? What products? What platforms?

The answers to those vexing questions will be revealed only after publishers invest the time and money necessary to develop thoughtful strategic plans that take into account local market conditions, the competitive forces arrayed around them, and the unique strengths and weaknesses of their respective organizations. Equipped with well-wrought strategic plans, publishers can invest wisely and confidently in opportunities to attract new audiences and revenue streams.

As mission-critical as strategic planning and audience building ought to be, these missions fail to be accorded the priority they deserve at many newspapers. Some newspapers delegate “audience” to the editor, who somehow is supposed to fix things by intuitively producing the “right” sort of content. Some publishers assign audience development to the circulation manager, who somehow is supposed to boost subscriptions while curbing cancellations. Some papers allocate audience development to the marketing department, whose staffing, research and/or promotional budgets often are the first to be cut in moments of financial distress. At many newspapers, these missions aren’t even explicitly on the radar at all.

When the development of transformative and delightful products is left largely to chance, the outcome is unlikely to be auspicious, because successful innovations seldom emerge from seat-of-the pants hunches, scattered responsibilities and episodic tactical skirmishes.

Success requires a well-researched, well-conceived, well-articulated and well-communicated strategic plan that is the responsibility of everyone in the building. At most newspapers, this approach not only would be transformative but also would make life more delightful than it has been in years.

© 2013 Editor & Publisher

Are newspapers losing ‘mass media’ mojo?

Print newspaper circulation has fallen to the lowest level since the 1940s and the lowest household penetration rate in modern history, raising the question of when a mass medium is no longer a mass medium.

Because a growing amount of news consumption is moving to digital platforms, the answer, as you will see by reading on, is complicated. Here is what we know:

As discussed here last week, U.S. publishers now are selling between 38 million and 43 million newspapers on the average weekday vs. 41 million copies on the average day in 1940.

Back in 194o, when broadcasting was in its infancy and print was the state-of-the-art source for news and shopping information, Americans on average actually consumed more than one newspaper per day. Consequently, the number of newspapers sold in 1940 equalled 118% of all households and actually rose to 124% in 1950.

In the intervening years, as illustrated immediately below, a host of demographic and technological disruptors has dropped newspaper consumption to the point that barely one out three households buys a print edition. Here is the trend (assuming 43 million in average daily circulation):

The ongoing decline in print readership raises the question of when a medium ceases to have sufficient critical mass to be considered a mass medium. Given average weekday newspaper circulation of 43 million, here’s a comparison of newspaper penetration with other media commonly found around the house:

Of course, newspaper content is no longer consumed in print alone. News and advertising produced by newspapers are widely consumed on computers, mobile phones and laptops.

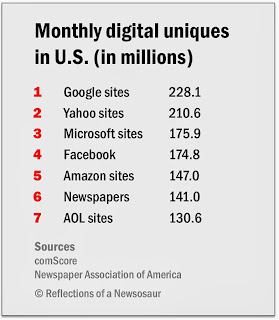

Based on data obtained from comScore, the Newspaper Association of America reports that 141 million individuals are consuming digital content from newspapers each month. With some 40 million homes taking print papers and more than one person often reading the same print edition, it is fair to assume that print readers represent a significant, but incalculable, percentage of the 141 million digital visitors cited by the NAA.

Setting aside the duplication issue, the 141 million online newspaper readers would be the sixth largest digital audience in the country. Here’s where newspapers fit in:

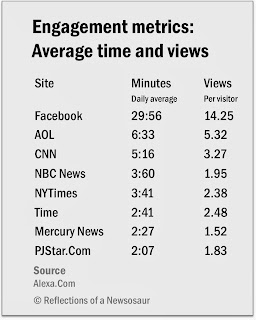

While audience size certainly matters, the next question is how deeply visitors engage with newspaper websites, which is a good indication of their utility to users and, thus, their value to advertisers.

As illustrated in the next table, news (and most other) sites are not nearly as engaging as Facebook, where Alexa.Com reports that visitors on average spend nearly 30 minutes per session and consume an average of 14.25 page views per visit. By comparison, visitors spend less than 4 minutes per session at the New York Times and NBC News sites. Engagement is even lower at local newspaper sites, as evidenced by the data below for the San Jose Mercury News, in the heart of Silicon Valley, and the Peoria Journal Star, in the heart of the nation.

The biggest question of all is how well a digital publisher monetizes the eyeballs it attracts. The comparison is not easy, because traffic-grabbing sites like Google, Yahoo, Microsoft and Amazon draw their revenues from different sources than those pursued by newspapers – namely search, software sales and commerce.

But the display-advertising models at Facebook and AOL, which happen to bracket newspapers in the size of their respective digital audiences, are reasonably comparable to those employed by most newspapers. Here’s how sales volume compares:

In 2012, Facebook generated $5.1 billion in revenues, newspaper digital media generated an aggregate $3.4 billion in advertising sales and AOL generated $1.4 billion in advertising sales. (These figures don’t include the fees that some newspapers charge for digital access or the subscription fees that AOL charges to those who use it to connect to the Internet.)

A comparison of the revenues among the three contenders shows that newspapers in 2012 generated $23.90 in advertising revenue per digital subscriber, as compared with $29.18 for Facebook and $10.72 in ad-only sales for AOL.

While newspapers can claim to be competitive in attracting a large number of unique (but not necessarily deeply engaged) visitors for their digital products, the real problem is that their print business – which still delivers 75% of the industry’s total advertising sales (and perhaps 90%, if you count print circulation revenue) – has been contracting relentlessly for more than seven years.

As illustrated in the next chart, print ad sales, which peaked at $47.4 billion in 2005, were only $18.9 billion in 2012, representing a 60% decline for the period. Meanwhile, digital ad sales grew 66% from $2 billion in 2005 to $3.4 billion in 2012. While robust, the rate of digital advertising gain at newspapers was barely a third of the 193% growth achieved by the over-all online industry, where the Internet Advertising Bureau reports that revenues surged from $12.5 billion in 2005 to $36.6 billion in 2012.

The $27 billion drop in newspaper ad revenues between 2005 and 2012 is equal to the annual sales of more than five Facebooks. While newspaper revenues have fallen in every quarter since the first three months of 2006, Facebook just announced that its sales in the first nine months of this year surpassed the revenues for all 12 months of 2012.

Where does that leave us?

With aggregate revenues this year likely to remain comfortably north of $20 billion, the newspaper industry remains a substantial business. But it is less than half as substantial as it was a scant seven years ago.

But the population of steadfast loyalists is dwindling, as modern consumers take advantage of the digital media to customize the news, entertainment and information they ingest. Given shifting consumer preferences, newspapers need to think differently, if not to say obsessively, about how to serve – and profit – from individuals who don’t look, think or behave like traditional subscribers. Unfortunately, most newspapers don’t.

But the population of steadfast loyalists is dwindling, as modern consumers take advantage of the digital media to customize the news, entertainment and information they ingest. Given shifting consumer preferences, newspapers need to think differently, if not to say obsessively, about how to serve – and profit – from individuals who don’t look, think or behave like traditional subscribers. Unfortunately, most newspapers don’t.