Vaporized: $13.5B in news stock value

To put this in perspective, the vaporized value is greater than the enterprise value of the Tribune Co. or the combined value of the McClatchy, New York Times and Media General publishing companies.

The vertiginous drop came at the same time the Dow Jones industrial average soared to an all-time high and other market indicators gained by healthy double-digit percentages.

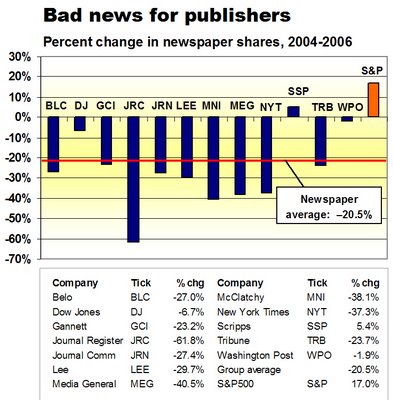

Of the 12 publicly held newspaper stocks traded in 2004 that remain with us today, only the shares of Scripps have advanced. Scripps’ 5.4% gain contrasts with the 15.6% advance in the Dow industrials in the same period.

Scripps shares are going in a different direction from the rest of the newspaper industry, because the company has been moving aggressively to build its cable TV, broadcasting and online holdings. With only about a third of Scripps revenues coming from the newspaper business, it probably shouldn’t even count as a publishing company any more.

Although the shares of Dow Jones, Gannett and Tribune gained in 2006, those companies and the rest of the industry have been in negative territory since 2004. The biggest loser, in the last two years, by far, was Journal Register Co., whose shares plunged 61.8%. The Washington Post Co., which has been diversifying away from its eponymous newspaper, suffered the smallest decline at –1.9%. Details are in the table below; calculations are based on 2004 closing prices adjusted for dividends and splits.

At the end of 2004, newspaper shares roughly paced the performance of the S&P 500, an index measuring the performance of a broad array of stocks. In the last two years, however, the S&P 500 rose 17% while the publishers melted down.

The sell-off has been prompted by declining readership, falling revenues and rising concern over the industry’s ability to respond effectively to competition from the new media. As Goldman Sachs recently noted, 2006 likely was the first “non-recession year” in history in which newspaper revenues declined.

Publishers, investors and others who care about newspapers rightfully were (and should be) worried about changes affecting the long-term economics of the industry. It is completely rational for the market to discount stocks in response to a real or perceived deterioration in their fundamentals.

But the collapse of newspaper share prices arguably was accelerated by a panic sparked by several large investment funds that suddenly soured in unison on the publishing stocks they once accumulated with confidence and zest. When they fell out of love with newspaper shares, they (and the stocks) fell hard.

Institutional investors for the last two years have pressured a succession of iconic newspaper companies – including Dow Jones, Knight Ridder, the New York Times and Tribune – to put themselves up for sale in hopes of realizing greater value than the stock market accorded their shares.

To date, Dow Jones and the New York Times have resisted the pressure to peddle their assets. Tribune has been trying, without much evident success, to find someone to buy part or all of it. And Knight Ridder succumbed in what proved to be a disappointing financial outcome for its faithful investors.

Growing investor pressure has terrorized and dangerously defocused the executives of publicly held companies, whose compensation and job security are tied directly to the value of their shares.

Instead of navigating their businesses through the most difficult environment they will ever know, the executives have been forced to spend disproportionate amounts of their time on investor relations, financial engineering and ill-considered expense cuts that could imperil the long-term health of their franchises.

In all likelihood, newspaper companies would have performed better in the last two years, if publishers had spent more time rigging their businesses for the digital age and less time truckling with the pin-striped barbarians at their gates. Better operating performance probably would have led to higher share prices, too.

As big a fan as I am of free enterprise and free speech, I don’t think anyone has the right to cry “Fire!” in a crowded theater while decent and well-intentioned people (newspaper executives) are trying to shepherd the innocents (readers, employees and advertisers) to safety.

But that’s essentially what Wall Street has been doing for the last couple years.

5 Comments:

It's interesting that when McClatchy put the Minneapolis Star Tribune up for sale, it only got $530 million for a paper it had purchased 8 years ago for $1.2 billion. Losing 58 percent of its value in 8 years is beyond panic selling.

On target analysis. Is this another argument for private ownership? Will it take private ownership to make newspaper companies competitive in a new media world?

The hyenas crouched just outside the building would be the blogosphere, where watching MSM/print burn has deteriorated into sport.

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. I sometimes think we in the industry have talked ourselves and investors into this, but you put things into great perspective. Perhaps the rest of us have bought into the chorus of doom-sayers. And you are so right. We have the tools in our hands to fix this. I am no longer in professional media, but I have been working in college media for the past 23 years, and I find it amazing that the young people coming up use all the new technological tools at their disposal -- until it comes to their beloved campus newspaper. There, the print editor give a grudging nod to the web and go on about their business as they have been for more than 100 years on this campus. There are glimmers of hope, and I nurture them as best I can, while hoping that this generation coming up will help the white elephants do exactly what you recommend!

Great article.

Are there any former Knight Ridder employees reading this blog? Yes? Then perhaps you can answer my question:

How many Knight Ridder employees were there when Knight Ridder first put itself up for sale in Nov. 2005? (+- 500)

Send me a message

davou at att dot net

Post a Comment

<< Home